Daniel Buckley, Composer

In the middle of the night in 1979, Daniel Buckley went from thinking about being a composer to doing it.

(Click HERE for examples of Buckley’s music and here for press links. Visit Daniel Buckley’s Soundcloud Page for more full length examples)

He’d been reading an article about Brian Eno and how he was using tape loops of various lengths to generate repeating but transfiguring pieces of music. Looking around the room he could see that he had what he needed. Percussion and wind instruments from around the world. A jew’s harp. The sound of his own breath and voice.

A Dokorder reel to reel tape deck with two speeds, sound on sound and echoplex. Two mismatched cassette decks, a microphone and 4-channel mixing board from Radio Shack. A plastic splicing kit with single-edge razor blade. Instant tape loops!

The source material was ungainly, the assembly crude and imprecise. The edit points clunked. It was never clean. The levels were all wrong. But in layering the tracks, and later dumping additional tracks onto the cassette machines, he built up complexes of strange and frequently cringe-worthy sound. His girlfriend awoke to find him holding a tin whistle out in the air, letting the tape pass over it 4-5 feet from the reel to reel to keep tension as a long loop of magnetic recording tape played out. “While you’re up could you reach the record button on the first deck?” he asked. She shook her head, pressed Record and headed back to bed.

Over the next few years he experimented with sound and recording, adding the banjo, synthesizers, toys of all sorts and harmonica to his preferred soundscapes, while moving from tape loops to multitrack music making. The advent of sampling keyboards made logical sense after doubling and halving tape speeds to produce higher and lower octaves. The ways in which the ear derives information about relative harmony through mathematic relations of pitches became a way of creating canon and irregular rounds as interpreted through the sampling keyboard. Likewise the ability to loop and to exactingly trim those loops became a strong draw in Buckley’s evolution of musical language.

As did language itself. Early on Buckley fell under the spell of human speech – the rise and fall, the rhythms, the melodious tones of preachers and politicians, the dull roar of newsmen. It was not long after he started composing that Buckley learned of the Jonestown tapes – recordings of Jim Jones and his followers in their day-to-day life. Haunting, horrifying, mundane and mystical, they became the fodder for decades of experimentation that carries on to this day.

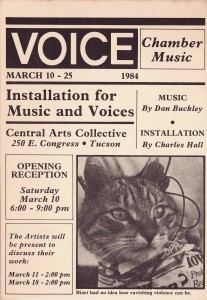

Buckley composed prolifically through the 1980s, writing music and doing sound design for theater, dance, fashion shows and video productions. He collaborated with many visual artists at Tucson’s Central Arts Collective during the 1980s, among them Rosemary Geseck, Emily Basham, Charles Hall, Allen Maertz, and Michael Cajero. Inspired by an elderly flute-playing customer from his days in a Tucson record store, Buckley created music “for my own amazement.” It was a lighthearted time that produced such comedic works as “The Carnival Girls” and “Eyes On the Cornbelt.” It was also a time when he was developing such performance art personas as Blind Lemon Pledge and Lonesone Jack Underpants.

Buckley wrote his first opera, “West],” in 1987 with a grant from the Southwest Interdisciplinary Arts Fund. Based on stereotypical concepts of the American west as expressed in movies and bad television, the comedy surveyed the west’s human landscape from the conquistadors to modern times. Toys and a small chamber instrumental cadre accompanied the vocal quartet in this chamber opera.

Gunfight scene from “West” (Michael Anderson, left; Helen Williamson Thoenes, center; Bob Einweck, right)

1987 also marked a career change. After a fairly successful run as a composer and performance artist, Buckley went to work as a music critic for Arizona’s longest continuously published newspaper, The Tucson Citizen newspaper. Because management considered it a conflict of interest, Buckley was forbidden to work with local musicians or perform in Tucson. The tradeoff was an opportunity to help other artists in the community and provide a framework for their work within the national arts scene. Buckley continued with the Citizen until the paper’s close in 2009. He has also been a contributor to Stereophile Magazine from the mid-1990s to the present, writing mainly about contemporary classical music.

To feed his composing habit during his forced period of silence in Tucson Buckley turned to electronics, sampling and sound manipulation to expand upon his musical direction and develop his voice.

The early 1990s saw Buckley experimenting with excitation of strings, continuing the moody landscapes that started to take shape during the composition of “West]” and laying the groundwork for his Jonestown opera. Using standard guitar slides and tin whistles, Buckley began to bow the strings of the banjo and a metal-strung baritone ukulele to excite the overtones of the strings. He recorded these eerie sounds, fed them into sampling keyboards and transposed them in pitch to generate an array of new, exotic sounds. Using sampled prepared pianos, eerie chunks from prior works and electric guitars, a new series called “The Prevailing Westerlies” was born.

In the mid-1990s he composed “Soul Seduction: A Jonestown Scrapbook” for the Kronos Quartet. The darkly-funky, four-movement work, which primarily featured pizzicato strings, included a tape audio track with the unaltered voices of Jim Jones and his followers. The string quartet parts were in Hungarian modes a la Bartok to underscore the insidious undercurrent of Jones’ “healings and blessings.” A suite based on the Apollo moon landings also dates from this era.

The first decade of the 21stcentury was a time of retooling and focused musical study for Buckley. In much more serious ways he dove into the art of digital recording, sound manipulation, sampling and even DJ techniques to forge the elements of a new style. Various aspects of the Jonestown project continued to occupy the bulk of the decade’s work in one form or another, along with numerous etudes (studies) in various forms, sonic colors and electronic treatments.

From the beginning Buckley’s evolution as a composer has been paralleled by growth as an audio engineer. Over the years, Buckley learned how to best record and edit music of many types, how to choose the best microphones and techniques to capture the sound, and how to mix the resulting tracks together. He learned the tools of the trade, from compressors and equalizers to filtering and sound-altering processors and software. He experimented with digital and analog delay, time stretching and looping technologies. And he learned the ins and outs of digital samplers and synthesizers.

Through the Jonestown Institute in San Diego, Buckley was able to acquire ALL of the recordings made by Jim Jones and his followers, from Jones’ days in Indiana to the final death tape. The Jonestown Institute also provided databases of transcriptions of each tape. Over time, Buckley began breaking them down into chunks to feed into samplers and electronically modify. That slow, gradual process is still in its infancy as there are hundreds of hours of tapes to go through. As he progresses slowly through that preparation process Buckley is experimenting with vocoders and autotune technologies to turn speaking voices into singing voices.

As the second decade of the 21st century dawned, Buckley has been intensely involved in work leading to “The Jonestown Dances,” also called the Totentanzes (dances of death) – a suite of dance music using elements from the Jonestown tapes. The Jonestown mass suicide took place in the heart of the disco era, and Buckley is reflecting that in this series.

At the same time, Buckley has been refining both his concept for the eventual Jonestown opera, and his skills to bring that work a never before seen combination of multimedia theatrics and electronic alchemy.

He still likes things that don’t quite line up. While digital technology has afforded a much broader palette of sounds and the ability to fix every mistake, it is those mistakes that often reveal the idiosyncratic beauty of sound – something Buckley learned early on from Brian Eno.

Buckley uses a broad range of software to create his electronic pieces, among them MOTU’s Digital Performer, Avid’s Sibelius, MakeMusic Finale, Bias Peak Studio, Native Instruments Komplete, Kore, & Traktor Pro; Izotope Alloy, RX & Ozone; Waves GTR, Propellerhead Reason & Record, as well as software synthesizers and keyboards from Arturia, Synthogy, Applied Acoustics, Rob Papen, Ohm Force, QuikQuak and more. He also uses sound alteration and filtering software from Antares, Bias, Celemony, Nomad Factory, IK Multimedia, AudioEase, and PSP, as well as G-Player, Kontakt, Play, Aria, UVI, Vienna Instruments Pro and Mach-V samplers.

In addition, Buckley plays electric guitar, lap steel guitar, banjo, baritone ukulele and a broad range of ethnic wind and percussion instruments, with predictably unpredictable results on all.